It was the 100th anniversary of my late mother’s birth when I stumbled across the Trans-Canada Ultra. This was starting June 2022 from Whitehorse in the Yukon to Newfoundland—some 12,500 km of cycling across Canada.

Advertised as “The hardest and longest self-supported bike race in the world” my interest was piqued. I still had my residual fitness from racing the Tour Aotearoa and had always wanted to cycle across my country of birth. I was also chaffing for a return after the 2+ years of New Zealand being locked down due to Covid. These five years were the longest period since I left Canada in 1983 that I had not returned. Another attraction was this was the first time the event was run and these are the best rides to take: you have no idea what the ride will be like!

After getting my wife Lis’ approval, I entered and, 51:23:17 and 12,362 km after starting (238 km/day), with 82,454 m of climbing, I won—or should I say beat the only other person crazy enough to start!

With a ride of such magnitude it was really hard to know where to start in describing it. So I’ve taken an unusual approach: I asked a number of people who followed my daily Facebook posts what three questions did they have. The following is an attempt to give a picture of this great adventure based on these questions.

How did you get to the start?

The first challenge was actually getting to the start at Whitehorse. I had my flights all arranged but then I got Covid so had to cancel. When I began to feel better I knew that I would be able to ride but then all the flights from New Zealand were fully booked! So I wait listed myself on flights to Los Angeles, San Francisco and Vancouver.

Wednesday night at about 21:30 I got a call from Air New Zealand saying they had a seat for me Friday morning to Vancouver so I took it. 36 h was enough time. My wife Lis drove me the 2 h from Golden Bay to Nelson Airport and then flew to Auckland and Vancouver where I overnighted with my friends Anke and Otto before flying on to Whitehorse. 44 h door-to-door.

What was the route?

|

|

The ride started in Whitehorse Yukon and ended at Cape Spear Newfoundland which is the easternmost point in North America. As you can see from the route map below, it did not exactly take the most direct path. We went south along the mountains of the west coast to Vancouver, then east across Rocky Mountains, then continued across the country. This included a 600+ km loop around Prince Edward Island.

While the web site advertised that there was some 100,000 m of climbing (11 x Mt. Everest) this was generated from the GPS data at the planning stage. The actual climbing according to my Garmin was 82,545 m—only 9.3 x Mt. Everest.

The route was primarily paved. A number of times I was on unpaved roads/tracks etc. and it subsequently transpired that this was usually an artefact of the RideWithGPS export algorithm where they shifted us over to an adjacent trail from the paved route that the organiser had originally identified. This led to a long hard ride on an ATV trail into Toronto, and a nasty night ride on another ATV trail after leaving Prince Edward Island. The joys of riding the first edition of a race! At least future riders will hopefully be spared from this.

The organiser did an incredible job of finding us the safest possible route across Canada. I cannot imagine how many hours it took—Louis-Eric commented that it was five years in the planning and I believe it. There were only two sections where I felt unsafe—west of Sault Sainte-Marie and on the last day into St John’s (see below). It is an incredible feat to travel so far so safely. This led to some long diversions, such as at Regina, but it was in the spirit of avoiding unsafe roads with a history of cyclists being taken out so I was grateful for the efforts.

How safe was the route?

Safety is in the eye of the cyclist but I think the organiser did an incredible job of finding us the safest possible route across Canada.

When we engineers are looking at cyclist safety we have to keep in mind the tolerance for stress which is along the lines of that shown below. Anyone who undertakes a road ultra-endurance cycling event would by nature fall into the ‘Highly Confident’ category. If you don’t, then you shouldn’t ride. I would put myself at the very right of the highly confident—probably in the 0.01%.

It is also important to contextualise the ride: cycling over 12,000 km is what only a small number of cyclists do in a year. So when considering safety, it is not just over this event, but relative to over a year.

With those caveats in place, this is the third safest ultra-endurance road race I have even done. The only safer ones are those organised in Europe by Andy Buchs where there is a much denser road network so Andy is able to find safer alternative routes, even if they do end up taking you through a sandy orchard late at night.

The Indian Pacific Wheel Race across Australia was my worst cycling experience ever. I had cars passing and throwing beer bottles at me; heavy trucks on a completely empty road in the outback would not move over a cm and insisted on passing so closely—and fast—that more than once I was blown off the road onto the verge. Australia is the only country I will never cycle in again.

Other races like the Transcontinental see you choosing the route and invariably you will make a bad choice. Even if you didn’t, in the two that I rode we finished in downtown Istanbul which is not a great place to ride—especially after dark on a Friday night!

In some places on the route the Trans-Canada Highway is the only option available—for example over Roger’s Pass in the Rockies and west of Sault Sainte-Marie. In both instances there are a lot of trucks.

The route in the Rockies from Revelstoke to Radium Hot Springs was busy and I found the noise from the trucks a bit overwhelming for my brain injury. I didn’t feel especially unsafe, just discombobulated. So I decided to continue riding over night and the road was virtually empty. If you are not confident about riding this section, just do it at night and you’ll be fine. Be sure to have a dynamo so you don’t run out of light!

There was only one road to Sault Sainte-Marie: the Trans-Canada Highway. In the rider handbook this is noted as a particularly dangerous section with a prevalence of logging trucks. This was no exaggeration.. There was no rhyme or reason to the shoulder widths: they varied from 1-2 m in places, to 0.5 m (as in this photo) to absolutely none. They were  numerous and travelling at speed. The drivers seemed oblivious to Ontario’s law that they are supposed to pass cyclists with a 1 m space. Or perhaps they were focusing on the “where practical” part of the law, having decided that it was impractical to move over. I had been standing on a shoulder and was at a low speed on the edge of the road when this truck blasted past with horn blaring for one of the closest calls I can ever recall. Not fun. I probably should have done this at night.

numerous and travelling at speed. The drivers seemed oblivious to Ontario’s law that they are supposed to pass cyclists with a 1 m space. Or perhaps they were focusing on the “where practical” part of the law, having decided that it was impractical to move over. I had been standing on a shoulder and was at a low speed on the edge of the road when this truck blasted past with horn blaring for one of the closest calls I can ever recall. Not fun. I probably should have done this at night.

I was on the road into St John’s just after rush hour and the traffic volume was still quite heavy. It had also been raining which meant one had to be extra  careful—at least the visibility was good. The road was way beyond dangerous. There was not only no shoulder, but the pavement edge was often broken and it pushed you out into the traffic to try and avoid the risk of losing control. There would have been upwards of 750 veh/h on the road, many of them light trucks, and most were in excess of the posted speed limit. It was horrible. Hopefully Louis-Eric will find another option!

careful—at least the visibility was good. The road was way beyond dangerous. There was not only no shoulder, but the pavement edge was often broken and it pushed you out into the traffic to try and avoid the risk of losing control. There would have been upwards of 750 veh/h on the road, many of them light trucks, and most were in excess of the posted speed limit. It was horrible. Hopefully Louis-Eric will find another option!

Other sections had different challenges: hills, winds, bugs, etc. but for me these are all just part of the adventure. I would not let concerns about safety put me off riding the route. There are far worse, including many people’s daily commute!

Was it a Race?

No and yes.

With a 51:23:17 finish for 12,262 km (238 km/day) with no rest days, you can see that I rode it pretty hard … I don’t think that I could have done any better. I was over 8 days ahead of the other rider with a ~800 km longer course (he was diverted because of fires in Newfoundland and also lost time because of a broken bike).

The ‘Grand Depart’ was originally planned for June 11th but the only starter was Henri Do from Montreal. Myself, and the other three entrants did not make the start line. I had got Covid so had to wait to recover. The other three did not show up for one reason or another. I started two weeks later. So in effect we had two people riding what we call ‘Individual Time Trials’.

As with all these events, I had three distinct goals:

- Don’t injure myself;

- Finish; and,

- Do the best that I can.

Having said that, everyone who knows me recognises that I am pretty competitive and set myself stretch goals. I rode as hard as I could without blowing myself up. So I was racing myself, but also Henri.

I saw that he averaged 220 km/day over the first weeks so I set myself the personal goal of riding an average of 230 km/day. This would give me a ~500 km advantage in distance over him towards the end of the race when each of us would do a push to the finish line. I had heard that he was able to do big 700+ km pushes, compared to my ~450 km ones. If it came down to it, I would have a shot at finishing ahead of Henri (my last day push was 452 km with 4709 m of climbing).

As it transpired, Henri had bicycle issues and other challenges, including worse weather. By the time I was in eastern Quebec I knew that even if I backed off the pace I would still finish ahead of him. But that didn’t change my goal of working hard to finish the best that I could. So I rode hard to the end just to see how well I could do. In the end, the ‘race’ was first against myself, then against Henri. As it should be.

What were the rules?

The rules of the event were the standard bikepacking rules. They can be summarised as do it 100% on your own with integrity.

We are to be totally self reliant. This means that we cannot accept any outside help that the other riders don’t have. So when the Shimano Representative offered me gloves and bibs at the bike shop in Magog I had to decline as Henri did not have the same offer. When a guy offered to leave me food and water outside his farm down the road in Saskatchewan I had to decline for the same reason.

We had to navigate ourselves 100% on the route. If we went off the route, we had to return to where we missed it and repeat.

We were allowed to visit two friends en-route, but had to pre-identify them before we started. Otherwise it was only staying at commercial places, or private homes where the other riders could also stay.

Unlike in New Zealand, there was no requirement to stop for 6h every 24h for rest which I liked. If there is a good tailwind it’s hard to stop—especially if you know that tomorrow it will be a headwind!

Why did you do it?

This is a question which I am asked often. Usually presaged or followed by ‘what is the prize money?’, ‘who are you fund raising for’, etc. One friend put it “what makes an old man (I am 62) go on such a challenging journey?”

There is no prize money, medal or even a T-Shirt. I will say that after the race I had lunch with the organiser Louis-Eric in Toronto and he gave me a pair of Canadian cycling socks, but this is not really why one does these sorts of ultraendurance events.

I do them for totally selfish reasons: I like to be alone riding my bicycle. Hard.

I find immense satisfaction from setting a goal and meeting it, especially when it is something that I’ve never done before.

For example, I’ve done lots of 300+ km days; numerous 400+ km ones, but never 500+ km. I was close to that when racing across Australia in the 2017 Indian Pacific Wheelrace but stopped when I hit 473 km because it was too hot and continuing would have caused damage. When riding from Revelstoke I rode some 240 km to Radium Hot Springs, felt good, so decided to continue on to Banff over night. After breakfasting at 6 a.m. I still felt good so pushed on and after 536 km reached Calgary. Since I rode 25+ h with stops for food etc. this effectively took two riding days of 268 km each, but it was special to knock off 500+ km in a single push. Especially when I followed it with a 300+ km day.

The rides invariably reward you with stunning scenery which I am humbled and grateful to see. Here is one example—some of the many incredible sunsets I saw.

|

|

|

|

So I guess I do it for the mental, physical and emotional challenges that these rides present. Each day I have this feeling of deep gratitude to be out there doing what I am doing.

It is just you and your bike. I appreciate the beauty of nature and the solitude. I love the sense of the unknown; new places and not knowing what will happen or how you will deal with it. Such as when something goes wrong and your bike breaks.

Did your wife actually agree to this?

Very much so.

We have been married for 34+ years and have each other’s backs. She knows that these rides, while physically challenging, provide me the mental and emotional relief that keep me going. I even managed to convince her to come to Canada after the ride and we spent a few weeks in Ontario holidaying, in part revisiting parts of the route that I blew through quickly and wanted to see at a leisurely pace. Below this is Lis out for a ride at Toronto’s beaches. No surprise, mine is the larger ice cream!

How did you train?

With a ride like this you are at a greater risk of going in over trained and tired than under trained. The demands of pedalling each day for so long (I averaged about 12 h/day of actual pedalling) are huge, and it’s really difficult to prepare the body adequately when one has a ‘normal’ life to live. So I train myself as best I can, and then expect to get into race fitness as the ride progresses.

I use the brilliant training platform Xert to manage my training. This is an adaptive program which looks at your goals, current fitness, and then proposes the training load that you should have—even down to specific workouts. Below is my Xert progression and training load chart from the beginning of the year.

I had the Tour Aotearoa in March and then after a recovery period I started training again. The circles show ‘breakthrough’ sessions where I set new performance standards. The large pink bar in early May is where I tried a virtual Everesting but quit after about 12 h because the software I was using had a bug in it. I figured another Everesting was a good way to train for long days. This was followed a few weeks after by a complete break when I had Covid, then some easy training building up to the race start.

The training had two elements. I would race 2-3 Zwift races a week of about 40-60 km for high intensity workouts, and then do some low intensity steady state riding for the other sessions, often also on the trainer. After I got Covid being on the trainer is the safest way to recover: you ride and then as soon as you feel tired get off. Can’t do that if you are out on the road.

When I started the event I made sure to take it easy so as not to stress my body too much, although I did end up riding further in the first days that I had expected because I felt OK. After a week or so I had my race fitness and was confident that there were no Covid issues so was able to open it up.

How did you logistically prepare for the race?

I sat down and followed the route carefully to identify places to resupply. I put this information into cue sheets with a running kilometreage. I have the distance between supply points, as well as the cumulative distance. When there is accommodation I also put in the phone number. This allows me each day to see what is about 200-250 km away, what options there are for stops in between, etc. I don’t put everything in, usually skipping places less than 50-60 km from the next one. I print the sheets on waterproof paper and then laminate them.

Since the ride was starting in the sparsely populated Yukon, I took some dehydrated food and energy/protein bars with me. The dehydrated food was selected based on the meals not needing boiled water as I did not have a stove. I used these sparingly and only as needed when no other options were available. I actually finished the race with one unused bag.

Since the ride was starting in the sparsely populated Yukon, I took some dehydrated food and energy/protein bars with me. The dehydrated food was selected based on the meals not needing boiled water as I did not have a stove. I used these sparingly and only as needed when no other options were available. I actually finished the race with one unused bag.

I knew from experience that I would need to have my bike serviced after about 4000 km. I identified bicycle shops in Canmore (Bicycle Cafe) and Magog (Ski Velo) which were top notch and were able to supply the key bits that I wanted to be replaced (new Specialized Sawtooth tyres, Dura-Ace chain, pads). Since it was against the rules to pre-organise things before we started, I only made the arrangements for servicing after I started the ride. Chapeau to both for your great support!

|

|

I also downloaded onto my phone some essential apps.

- OsmAnd+: This is a mapping program which allows you to have maps stored on your phone so work anywhere. I downloaded the GPX tracks for the ride and then OsmAnd+ allows them to be followed. What was particularly useful was the overlay with accommodation points of interest. This allowed me to identify accommodation in towns (particularly large ones) which were on or close to the route.

- RideWithGPS App: This was a backup to OsmAnd+. Used it when there was a route change and I had not updated my Garmin or OsmAnd+

- Epic Ride Weather: This app allows you to load the GPX route and then forecasts the weather based on your projected riding speed. Great for knowing if there will be rain/headwinds etc.

- Booking.Com: For lazy booking of accommodation.

- iOverlander: For finding bivying/camping spots.

I downloaded lots and lots of podcasts for listening to, the Bible, and music.

For payments, I had a Canadian bank account which I used for most payments with the debit card. I had two credit cards; one in my wallet and a backup hidden in my bike bag. Good thing because I lost my wallet in British Columbia!

For communications, my New Zealand cell phone provider had a roaming arrangement with Bell Canada. This was great most of the time. As a backup I used the Knowroamng eSim option with a 10 GB data package. This was ESSENTIAL as between Knowroaming and Bell I had data coverage for most of the trip. Canada is a big country and you can’t rely on one provider. Most of the time there was good coverage—at least when it was needed!

A side comment on travel insurance. It was interesting that the New Zealand travel insurance policies all exclude bicycle racing from their coverage. Bicycle touring is acceptable, not racing. Fortunately, this was a brevet which is not a race ![]() Be sure to check the terms and conditions on your travel policy if you are considering events such as this!

Be sure to check the terms and conditions on your travel policy if you are considering events such as this!

What was your setup?

A detailed video overview of my bike setup is here. Key details below.

- Bike: Specialised S-Works Diverge carbon gravel bike. The route definitely calls for a gravel bike and I was really happy with mine. Features:

- Absolute Black oval chainring. Essential for long distance riding.

- Connexis (or Dura Ace) chain.

- Specialised Sawtooth tyres (42 Front/38 Rear). Perfect choice as handled the range of conditions. Would not have wanted to ride this with the 28s I used for the Transcontinental and North Cape-Tarifa races. I run them tubeless with Finish Line sealant.

- Stages power meter.

- Shimano Di2 shifting, including on aero bars.

- Profile Design T1 aero bars with 50 mm lift.

- 3T aluminium handlebars. After breaking my carbon handlebars when racing across Australia, I would never use them again. Have Silca 3 mm tape with gel underlays on the bars.

- Shimano XTR M9020 pedals

- Cane Creek eeSilk Seatpost

- Specialised Format 143 seat

- Hunt front wheel with SON 32 dynamo hub with Flectr reflector tape on wheels. Brilliant wheel. Performed flawlessly and was still true at the end of the ride.

- Bags:

- Custom Stealth frame bag

- Porcelain Rocket seat bag

- Custom Stealth aero bar/handlebar bag

- Stealth ‘Frontloader’ bags:

- On back of aerobar bag

- On top of seatbag drybag

- Stealth feedbags on side of seat bag

- Blackburn gas tank bag

- Revelate design Egress Pocket roll bag on front of aerobar bag

- Revelate design mesh pocket on top of set bag frame

- Electronics and Lights:

- Garmin Edge 1030 Plus. I had an old Garmin 1000 as a backup if needed.

- Garmin Varia radar/light. This is ESSENTIAL equipment as it warns you when vehicles are approaching. I attached it to the retention strap on my Porcelain Rocket Seat bag. Since it only has about an 8-10 h running time, I ran a USB cable from the cache battery when it began to run low on the internal battery (not worth running down the cache battery if you don’t need to). Doesn’t work off the dynamo USB.

- Voltaic V50 dual-USB powerbank as cache battery. This is by far the best powerbank if you are running a dynamo. It takes a trickle charge while at the same time providing output. I found it best not to charge it at the same time I was running my Q-Tube lights (below) as they would draw power from this before the dynamo.

- K-Lite dynamo gravel light with dual USB supply which was in the top of my frame bag. I ran a splitter cable from the dual supply into the gas tank bag. One line was used to charge the Garmin 1030 on the handlebars; the other was for charging the phone or running the rear K-Lite lights. The second USB line ran to the V50 cache battery.

- K-Lite Q-Tube flashing safety lights. These are absolutely brilliant and run from the USB. I found that they drained the power of other things so disconnected the cache battery charging when they were in use.

- Lupine Pico light. This was my backup light and used when camping etc. I also could detach it and put it on my helmet for a camp light.

- OT Buckshot USB speaker. Let me listen to podcasts etc. while riding without the dangers of having ear plugs.

- Gear:

- Zpacks heximed tent with 2 spare tent pegs and carbon pole

- Montbell 800 down sleeping bag

- Sea to Summit ultralight sleeping mat

- Sea to Summit ultralight pillow

The full packing list of clothes, tools, etc. and where they were packed is here. The logic behind the packing was that the Revelate roll bag would be the one bag which is always taken off the bike when I need to rest (e.g. hotels) along with potentially the frontloader bag on top of the seat bag. Rest of the bags were on the bike for the full trip.

WARNING: The shuttle to Prince Edward Island may require you to remove the bags as they have a rack which fits through the frame. With my dynamo wiring running out from the frame bag this was not practical and managed to fit the bike into the boot of the vehicle.

What would you change from your gear if you did it again?

Not much. My kit has evolved over the years and I have it pretty well dialled in.

The K-Lite mount failed—it was 3D printed plastic—but I solved this using zip ties. Kerry has assured me he has changed the ‘recipe’ so won’t happen again. This is also why I had a backup light.

I would make a few minor changes to my ‘cockpit’ setup. This is shown below when I am also recharging the Di2 electronic shifting. I would swap around so that the Bluetooth speaker is on the right of the Garmin so I can easily access the Garmin power. I would have a temporary mount for my phone. A number of times I had to use it with OsmAND+ or Google for navigation and I didn’t have a good mount.

My Re-Skin anti chafing patches for the first time didn’t work well and came off too soon. Perhaps the adhesive is wearing out as I’ve had them for some time.

Mosquito spray was marginally useful, the mosquito shirt was essential. The flecks on the photo below are the blighters trying to get me in the Yukon.

It was very handy having the tablet computer with me for making my journal entries at the end of each day. Even more so for putting the revised routes onto my Garmin. But the weight was (relatively) substantial and it also required a larger power supply. A lightweight Bluetooth travelling keyboard would probably have sufficed, at least for shorter trips. But still nice to have the tablet when work meltdowns happened!

Is electronic shifting worth it?

Definitely.

The context of this question was my shifting failed about 150 km west of Sault Sainte-Marie when my battery level went from 70% to 0% a lmost instantaneously. It had begun shifting irregularly and I managed to get it into a ‘workable’ gear when there was complete failure. Once this happens you have no way of shifting the gears whatsoever. The gear had me spinning too much on the flat, and was very hard going up hills, but it was all that I had and at least I could ride the bike as a single speed.

lmost instantaneously. It had begun shifting irregularly and I managed to get it into a ‘workable’ gear when there was complete failure. Once this happens you have no way of shifting the gears whatsoever. The gear had me spinning too much on the flat, and was very hard going up hills, but it was all that I had and at least I could ride the bike as a single speed.

I got to Sault Sainte-Marie and Heather from Algoma Bicycles very kindly opened her shop for me the next morning on her day off to try and help. She didn’t have the right battery, and none were in stock at Shimano Canada. So this meant a wait of unknown length or riding single speed until such a time as I could get it fixed. Being the sensible person I am, I of course opted for the latter and rode away.

I identified a battery in Toronto and had it couriered to Owen Sound. I then rode some 450 km to Owen Sound single speed. If people can do 10x that distance on the Tour Divide I figured I could. I must confess that Manatoulin Island’s hills were particularly hard on my legs and they were fairly trashed when I got to Owen Sound. Brian from Forks Bikes had been alerted by Heather I was on my way and he unfortunately found that it wasn’t the battery! He went beyond the call of duty and the next morning had found that the cause was a pinched wire which probably happened when the bottom bracket was replaced in Thunder Bay. He rewired the bike and I was on the way again! I’ve recommended that future races be routed past his shop.

Had I been using cable shifters this would never have happened… But on balance I’m glad I didn’t have them.

The reason is that I’m 62 years old and electronic shifting is really kind to my old body. Seriously. When you are continually shifting manually I found that after about 3,000 km my hands begin to cramp badly and get sore. I couldn’t even begin to imagine what they would be like after 12,000 km. Pushing a button is just so much easier. This is the first time this has even happened in my racing and hopefully the last!

Did you ever consider quitting?

Not once. Of course there are bad times. You get cold, wet (like below), hungry etc. I was all of these and more. But I never considered quitting.

I’m a pretty obsessive compulsive person when I have a goal and if I’ve set my mind on something it will take a lot to stop me. For example, when I turned 40 I cycled across America and got ‘doored’ in Vermont. Broken collar bone, twisted knee, bruising etc. With only 400 km to finish my ride I did the sensible thing: got on my bike and rode the 400 km resting my arm on the handlebars. Broken leg? Yep. That would stop me. Arm? Collar bone? No, tis but a scratch as Monty Python would say.

The most difficult times were when my brain injury acted up. This is the legacy of a crash four years ago (see below). The ‘triggers’ are excessive noise and visual stimulation—which is one reason why I so enjoy night riding as there is little traffic and I often only see what is in my headlight. When it acts up I get panic attacks, headaches, and just want to run and hide. I was worst on rainy days when the noise of passing traffic—especially trucks—was amplified. I’d ride with ear plugs in but by the end of the day I was usually really done and my head needed to rest. I’d gauge some days by how many headache pills I needed and towards the end was a bit worried I’d run out of my special medicine. But these things would at most lead me to having an early stop for the day. Never quitting.

How did you deal with days when you didn’t want to ride?

There was not a single day when I didn’t want to ride. Seriously. Two mornings (in Manitoba and Quebec) it was raining so hard I (wisely) decided for a late start, otherwise I was on the bike at the first opportunity.

Do you have routines for arriving and departing each day?

Some riders carry cards reminding them what to do etc. and this might be of value. May have stopped me forgetting things!

When I stayed at motels the focus was on food and getting my clothes clean. For the former, I would try and buy 3 L of chocolate milk. 1 L was consumed on arrival; 1 L over the course of the night; and 1 L in the morning. Carbs, protein and rehydration. Great.

For an inexplicable reason motels do not have laundries in Canada. Only four times in the trip was I able to access a motel laundry. So I used the tried and true cyclist’s solution:

- Hop into shower or bath with clothes;

- Wash with soap/shampoo;

- Rinse and hang to drip dry;

- Wring out;

- Lay out in dry towels and roll up;

- Wring the water out inside the towel and let sit;

- Hang clothes.

In the morning they were clean and dry.

One side effect was that the shampoo/soap is thought to have damaged my shorts.

How did Covid affect things?

Canada was very different to New Zealand when it came to Covid. Very few people were wearing masks and most people just acted as if the pandemic was over, which it wasn’t. I followed Intel founder Andy Grove’s advice: ‘only the paranoid survive’ and so found myself wearing a mask, sanitising my hands, social distancing much more than the natives.

It was clear that many businesses had suffered as, particularly in rural areas, there were an awful lot of closed businesses. Most looked like they had been operating until recent times.

So on the face of it, one would not really have known that they were still getting over 20,000 cases a week. I did a test after the ride and was pleased not to have caught it.

How did the cycling compare between provinces?

Quebec is by far the most cyclist friendly province in Canada. Hands down.

I was told that this is because decades ago as part of a coalition government agreement, a policy was adopted that for each kilometre of new road, there had to be a kilometre of new cycleway. The result? La route verte (the green route) with 5,300 km of cycle paths. In addition, the planning and standards for cycleways were centralised as opposed to the rest of Canada where the local cities seem to be able to do things as they wish (or not at all). Below are a few photos of the different cycleways or wide shoulders I was treated to in Quebec.

|

|

|

|

|

|

There were other memorable cycle paths in other provinces. Vancouver has a great one heading west under the Skytrain. Calgary a brilliant one following the river. Regina around the lake. Toronto along the waterfront and east towards Montreal. However, none of these could touch on the scale, quality and extent of Quebec’s cycleways. I’ve suggested to the Golden Bay cycling group that a trip to Quebec should be on the cards.

For the other provinces there was the provision of wide shoulders. British Colombia, Alberta, Saskatchewan (and Newfoundland) had excellent shoulders. Things changed once you hit Manitoba where safe shoulders were few and far between. Same for Ontario. Nova Scotia was the most parsimonious when it came to shoulders, except for some reason on Cape Breton Island where there were a lot of good shoulders. Go figure.

What were the most scenic sections?

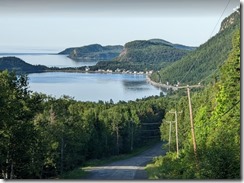

For me the most scenic things were mountains and water (rivers, lakes, coasts). Combinations of them? Jaw dropping. In terms of a specific section, Gaspe was by far the most beautiful single bit of road, with crossing the Rockies second.

Starting with mountains/water etc. Here are but a few examples. The top left photo below is Rogers Pass which was the highest point in the Rockies. I had a bit of chuckle as our local training often includes Takaka Hill which is about 800 m high—with a 10% grade for the length—vs 1330 m for the highest road of the trip. Result: riding the Rockies was not particularly difficult compared to New Zealand! Two climbs in Cape Breton were the closest to New Zealand, but they were only some 450 m high.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gaspe was this incredible area along the mouth of the St Lawrence to the Atlantic. We have a small parallel in New Zealand in Kaikoura—which has one advantage over Gaspe in the amazing snow capped mountains inland—but the scale of Gaspe is what sets it apart. You start off riding from Quebec City east along the water, and then cut inland before heading back to the water. Perce is a UNESCO site for good reason… the hole in the rock and beauty is just jaw dropping. The photos below don’t do the area justice. I’m planning on returning with Lis one day for a more leisurely visit.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

What was your most memorable or unusual bivy spot?

This was one that I could not answer as they were quite quite varied and many were unusual! Below are photos of some of them, starting in top left.

- Yukon: My first night I found a flat area 300 m off the road and bivied there. My third night bivied in a road rest area next to the toilet. My bike was parked in the toilet to keep the food away from the bears.

- British Colombia: A dog park

- Saskatchewan: A gazebo in the public park

- Manitoba: A post office (slept in two of them)

- Ontario: A picnic area in the national park (The rangers came at midnight and said I wasn’t allowed to camp there. I said no problem but when they heard that I had cycled 300+ km that day, and come from Yukon they said don’t worry—just leave early. Got to love Canadians!).

- Quebec: An RV park (arrived at 22:00 after the office closed; left at 06:00 before they opened. I tried sliding $20 under the door to pay but there was no gap!)

- New Brunswick: A public park next to the (mosquito infested) river

- Prince Edward Island: The deck of the tourist information centre (with the permission of the night watchman)

- Nova Scotia: An emergency shelter at the top of a mountain (which had power and was warm and dry)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

What were some of the unique things you saw?

I saw the full gamut of wildlife: arctic fox, beaver, bison, caribou, cayote, chipmunks, eagle, falcon, fox, moose, prairie dogs, snakes, squirrels, and a lot I don’t remember. But the most unique things were the northern lights and a blood moon (see below). Following those would be the array of incredible cloud formations.

|

|

|

|

What was your favourite lighthouse?

They all were! For some reason I’ve always found lighthouses to be special and I really enjoyed the variety of them that I saw on the ride. There was a brilliant poster on lighthouses of the St Lawrence which captured the variety, but unfortunately when I contacted the creator he said it was discontinued. I had a fantasy of dreaming about lighthouses in my office … Here are photos of some of them so you can see what I mean.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Which province had the best ice cream?

Quebec wins at this again. The quality of the ice cream—especially the soft serve—was incredible. Now don’t get me wrong, there was excellent ice cream available across Canada but Quebec was just special.

In terms of the best single ice cream, this goes to a hole in the wall shop in Saskatchewan which was in the middle of nowhere. It was still 40 C at 17:00 and I had been riding all day. I pulled in for some refreshment and they offered a cherry chocolate sundae. How could I say no? And it was … divine.

How did you find accommodation, food, etc.?

As mentioned earlier, I had prepared cue sheets for the ride which gave me every 50 km or so a supply point—where they existed. But generally, my approach was to ride and if I found somewhere to stock up I did.

For accommodation I used the OsmAND+ app where I had loaded in the track for the ride. Turning on the ‘Points of Interest’ (POI) for accommodation layer showed me *some* of the accommodation that was ahead. I say some because at best I’d say 20% of the places are listed. I’d sometimes use Google to also see what was ahead, or the Booking.com app. Wherever possible I’d not use Booking.com as they take a big commission and it’s best to book with the individual places where possible so they get more money.

The app iOverlander provides insight into informal and formal camping places. This was of most use to me in the Yukon and northern British Columbia where I could see a variety of options depending on how tired I was.

In the end though, it was really a case of riding until I was within about 10 km of my daily target and then looking for a place to sleep. If I could plan ahead, great. If not, I’d eventually find a place to stay or just bivy.

One side comment. When I wanted to stay in a motel it was REALLY difficult. It seemed that all of Canada was travelling. Even in the most remote places they were usually fully booked.

How expensive was it?

Very.

This is by far the most expensive ride I’ve ever done—and not just because it is the longest. As a number I would put the cost at CAD 250/day. This is in part because of accommodation costs—CAD 150 was a good deal on a motel (let alone the extortion in places like Calgary during the Stampede where it was over CAD 300 for a dump). But it would be easy to spend CAD 50 on a visit to the convenience store, a couple of times a day.

When you are in remote areas with no selection they set the price at what they want. This plate of scrambled eggs on toast was over CAD 20 in the Yukon. But with no restaurant for 200 km not much competition and I’d want to be paid a bomb to live there!

Was it difficult finding vegetarian food?

Most definitely.

Compared to Europe and New Zealand it’s tough to ride as a vegetarian. I don’t know how vegans do it!

Canada has a large number of fast food restaurants but the pickings are pretty slim. Submarines are the easiest to get and Subway restaurants are everywhere. Problem is that I ate so many of these I just couldn’t stomach them in the end. This was verified when I got to North Sydney to catch the ferry to Newfoundland. Subway was the only place near the terminal I could get something so I gave in and got one more sandwich. I ate half of it and felt so bad I went and had a chat to the toilet … Definitely no more Subway.

The main supply points were petrol stations/convenience stores. In Europe I could get things like drinking yoghurt, nice breads, etc. but not in Canada. One could at least buy protein drinks in most places, but otherwise the choice was often limited to egg salad sandwiches, chips, cheese and candy. And of course my staple chocolate milk. A particular ‘delicacy’ is a piece of cheese between two chips. Not exactly a healthy diet! But fuel is fuel and it got me to the finish line. Lost about 5 kg in weight.

|

|

When I could find a restaurant I ate a lot of vegetarian omelettes or French toast, which brings me to an observation on portion sizes. They are ridiculously large. I was in Gander Newfoundland and had cycled 75 km with no breakfast, after a big 250+ km day before with little dinner. I ordered an omelette, but was unable to eat the entire dish with the home fries and toast. I asked the very nice waitress if anyone had ever told them that they gave us too much food. ‘No, in fact they get the opposite complaint’!

How did you manage to do daily Facebook posts—even after long days?

It’s just something that I’ve always done. It’s part of my end of day routine and except for a few times, really is not a bother. I want my wife Lis to know what’s happening. Once in a while I’d get behind and then do a couple of days at once. These are adventures that I’d like to look back on one day and if you don’t document it when you are doing it, it is lost.

What happened to your clothes after the race?

I retired my shorts.

The backstory to this question starts in 2015 when I was racing Brussels-Istanbul in the Transcontinental Race. A photo was taken of me in Albania after having ridden from Venice with five nights of bivying. I looked a tad rough and my wife Lis said that she would burn my clothes when I got back to New Zealand. A friend of hers suggested that I be sent through the car wash first.

After finishing I had made sure to use the hotel laundry in St John’s to clean my clothes so I thought they were fine. But when my wife and I went for a ride in Toronto she commented that my shorts were indecent from the back. Although new when I started, they were very transparent after only 52 days of use. OK, those 52 days were the same as 1-2 years for most people but still…

I contacted Pactimo and they posited that it was the use of hotel shampoo and soap for the regular washing which caused the deterioration. They kindly offered me a replacement pair at 50% off the retail price.

In your posts you mention your brain injury. What the background and how did this impact you?

In the 2018 Tour Aotearoa I was doing really well when just after km 750 I woke up in a ditch in the Pureora Forest having somehow crashed my bike. Broken helmet, covered in blood, and bottom half of face split open. I ended up with a helicopter ride to Waikato Hospital, 4 h of facial reconstruction surgery, 33 stitches inside and outside of my mouth, and a traumatic brain injury (TBI) which has led to post-concussion syndrome. Could have been worse… I could have been killed or drooling in a wheel chair!

|

|

It took about three years for my injury to ‘settle’ wherein I have improved as much as I will. I’m fine much of the time but, as mentioned earlier, when certain triggers happen—specifically too much visual stimulation or noise, particularly of a certain pitch—it can send me over the edge with headaches and panic attacks.

One very problematic symptom for cycling is that there can come about a 1-2 second delay in processing information. This means that I may be 10-20 m further along a trail than I think I am. Trails/bad roads are also problematic because the jiggling causes me to become discombobulated. I have to stop for a while, close my eyes and ‘rest’ my brain or sometimes just pull the plug and sleep for a bit. I don’t like to take medications if I can avoid it.

In terms of impact, for one thing I don’t do mountain bike riding on trails anymore. Besides aggravating my symptoms, another crash would not lead to good outcomes on the rain front. On a day-to-day basis it is a case of monitoring how my brain is doing, and giving it a break from stimulation when it needs it—and before it goes too far. If I push it too much takes a lot of time/effort to recover. The most challenging times for me were rainy days with lots of truck traffic as the noise and wet roads were just overwhelming. Fortunately, there were not too many of these.

So I tell people with disabilities like mine don’t let them stop you. Find out the boundaries of the ‘box’ that defines what you can do and then keep inside the box as much as possible. Accept that there will be times you push things too much, but just accept those as the price you pay to continue to have adventures. You either master your disability or it masters you.

When did you get back on the bike after finishing?

I finished Thursday, flew to Toronto Friday, then went for a short ride Saturday and longer rides Monday once my wife Lis arrived. So no, I was not at all tired of riding my bike. I will, however, admit that my legs were a bit ‘heavy’ …

I’ll be entering into a 1-2 month ‘take it easy’ period as my body does need to recover from the ride. I also need to deal with a major shoulder injury that I’ve had for 6+ months and which the ride exacerbated. So it will be a period of some rest, shoulder rehabilitation, and easy cross-training.

What is next?

I have no idea! I am open to suggestions (except Lis says NO to an around the world). All I can say is that I still love to ride my bike…

Questions asked after my original post

How much time does it take each day to train for such events?

It really depends on your base fitness and what you want to achieve.

I’ve been riding my bike forever and typically do about 12-15,000 km/year of riding. So even when I’ve been off the bike for a while I’ve a residual base fitness which comes back pretty quick. So my typical training of about 10h/week provides a sufficient base which I can then ramp up as I move into the build and pre-race phases. I’d probably peak at about 15 h/week of training. But this is for someone who plans on riding really hard. If I was going to (say) only do say 175 km/day I would need less.

Could one use this route for touring?

Definitely. Many sections are common for cross-Canada cyclists, but in a number of places the organiser found alternative routes, usually because they were safer that the default Trans-Canada highway.

Would you recommend a bivy bag instead of a tent?

No.

When I did the Transcontinental Race (twice), North Cape-Tarifa, Kopiko and Tour Aotearoa I did them all with a bivy bag so that is usually my default sleeping kit. I put my sleeping mat and sleeping bag into the bivy and then roll the whole thing up. Means that I can quickly (and stealthily) roll it out, climb in and go to sleep without the hassle of pitching a tent.

This race was fundamentally different. The wilderness of Canada has mosquitos like nowhere else (except perhaps Alaska and Russia). It’s hard to describe the intensity of the swarms but in the 10+ seconds it took me to open my tent and climb in there would be at least a dozen mosquitoes with me. So as soon as I stopped I would don my mosquito shirt, lather on mosquito repellent and get the tent up as soon as possible. Eating etc. was all done in the confines of the tent.

In Northern Ontario the mosquitoes are also joined by ‘no see ums’ and blackflys, although they were nothing compared to the Yukon’s mosquitoes. If you want to appreciate Ontario’s blackflys, watch this award winning animated film.

What was your routine for protecting your ‘sit area’

At end end of the day I would clean with with a handy towel. I would then apply Assos Skin Repair Gel to the sit area. If I had any sores, I would treat them with Zinc baby nappy rash creme.

When riding, I normally used re-skin paatches but for some reason the adhesive wasn’t working well—at least in the heat—and they did not stay on. So I reverted to my DZ Nuts chamois creme, and when that was done I used some MucOff creme.

In the end, the above worked although it was a bit calloused. But given how many kilometres I cycled it was in great condition.

What helmet do you use?

I have a Bontrager Wave Cell helmet. This is similar technology to the MIPS based helmets. I like it because the venting on the standard helmets have sun the top of my head, while the wave cell does not.

Helmet technology changes and it’s good to have a helmet no more than about 3 years old. I always use the Virginia Tech testing results to ensure that I have a 5 star helmet.

What was the weather like?

It varied hugely along the ride. I will say that I was fortunate leaving two weeks after Henri Do as while he battled rain and cold temperatures in the Yukon, I was dry, but HOT. The peak temperature was 44 degrees C when I was south of Regina, and it was below 10 C at nights in the Maritimes. I planned for this range by using my down jacket and down pants as backups when it was really cold.

I didn’t have much rain across the prairies, but I definitely got hit by it once east of Quebec city.

Where were the longest sections without supplies?

Definitely in the Yukon and northern British Colombia. By the time I hit Sault Sainte-Marie in Ontario there were regular supply points all the way to the finish line.

One of the big challenges was that due to Covid businesses had closed. So while Google Maps showed a supply location, I’d get there and it would not be there. At the same time, there were a lot of intermediate supply points that were not listed on Google Maps (or OSMAnd+) and so I’d sometimes have nice surprises.

In the end, my strategy of always having enough food for 24h worked perfectly and only a few times did I find myself in strife.

Bivying vs Motels

My preference when possible is to stay in motels as the better sleeping helps with recovery and allow me to clean my clothes. However, I’d say about half the time I had to bivy somewhere as there were either no motels, they were full, or they had stupid prices. In Prince Edward Island there was one place available: a 3 star motel for $400/night. In your dreams.

With any event like this it is critical that you have a sleep system that you can use at any opportunity. As noted above, I used a tent which was great given the mosquitoes!

What were your biggest physical issues?

As noted above, my traumatic brain injury. But putting that aside, I had minor saddle sores in Manitoba. I think because the heat compromised my Reskin patches. I solved this with some zinc nappy rash creme and using Chamois Creme instead of my patches. After about 8,000 km I had some hand cramping issues off the bike—I had trouble holding cutlery. But these were passing. There was some numbness on the balls of my feet, but this wasn’t too bad. I had learned a oing time ago to deal with this by having orthotics with an raised pad in muddle under my plantia fascia (you can see the inserts have had a hard time!). If you suffer numbness in the feet this is an amazingly simple but effective solution. Any podiatrist can supply.

Finally, I had damaged my shoulder before the ride and it was even worse after 12,362 km. But this had nothing to do with the ride itself!

Do you recommend a dynamo system for events like this?

It depends on your riding style.

I like to ride long into the nights, often through the night. So having the independence of a dynamo setup allows me not to worry about having to stop. In the same way, the dynamo recharges my phone, runs my GPS, etc. But they are expensive.

For most people, a couple of 10,000 mAh power banks would suffice, particularly if you are ‘credit card’ racing where you will regularly stay in accommodation.

Can you share the statistics of your daily distances, etc.

Here is a chart showing the daily distances and the corresponding climbing for each ‘Day’. When I had big days of over 400 km, they spanned two calendar days.

I was pretty consistent around my 238 km/day average.

In terms of climbing, the 82,545 averaged out at about 1650 m/day. The distribution is below.

Finally, I averaged just about 11.5 h/day of actual pedalling, with three long pushes spanning two calendar days.

Any issues getting lithium SPOT GPS batteries?

The SPOT GPS which we use for tracking in rides like this use the Energizer Ultimate Lithium AAA batteries which last about 5 days. These are not always readily available—particularly in remote places like rural Canada. In anticipation of having difficulties, I adopted a different approach: I used ‘Eneloop Pro’ rechargeable batteries. I took two sets of four batteries, and recharged them using a USB recharger. These batteries would last about 3-4 days of riding before needing to be changed out. Only once did I run them too long and lose the signal. This is now my go to power approach for SPOT GPS’ since the lithium batteries are not cheap. And it’s better for the environment.

One caveat with the batteries. When I tried recharging them from my power bank or the dynamo on the bike they recharged too quickly compared to when plugged into the mains. So I ensured that I recharged them when staying in motels. It is on my list to find a similar small recharger which will do four batteries at once.

Is there a particular heart rate monitor you recommend?

Definitely. The Kurt Kinetic inRide H1 is by far the best heart rate monitor for long rides like this. The battery is listed as lasting 1000 h which is 10-20 x longer than my Garmin or Wahoo heart rate monitors. I only changed the battery once on the entire ride (and that was to be safe).

Great article Chris ! I’m really struggling to find a top heavy rain jacket. Could you be more specific which 7 mesh rain jacket you have used ? Assume you recommend ? Same Q for the rain pants ….Andy

ps congratulations btw !!

Hi Andy. I used the 7Mesh Skypilot (https://7mesh.com/skypilot-jacket). It’s a really well designed jacket which packs quite small. For my trousers I used the Ground Effect Splashdowns (https://www.groundeffect.co.nz/collections/all-products/products/splashdowns-full-length-commuting-rain-pants).

Even though the Skypilot uses the latest Gore technology, when the rain got superheavy it gave up and I got wet. This is just an artifact of having any breathable technology. Same for the trousers. Offsetting that, was the fact I could wear them as a cool/cold weather layer and I didn’t swelter.

So I’m still searching for the perfect solution for very heavy rains…

As a 64 year old thinking about starting the ultra experience, I’d like to know how much training time a day it takes to get ready for shorted events?

Hi Steve. I’ve added something at the end which may help… Not an easy question to answer!

Thanks Chris,

Another question if I may. Having trained so much, probably with a good diet, how do you cope with convenience food as far as energy requirements. I assume you are burning a lot of fats but also carbs on the (single speed/hilly) harder days.

Steve

Sent from my iPhone

The food is the biggest challenge, especially as a vegetarian. When riding I’m almost always at a low-intensity/fat burning zone, but after dropping some 5 kg there wasn’t much fat to burn! So I just fuelled myself with what I could get and listened to my body for what it needed. For example, I never eat chips but there were times when I craved them beyond belief–a sign I needed salts and fats. I also very rarely drank gatorade or similar drinks. Relied on food for electrolytes and it seemed OK.

Thanks for the reply. Have you thought of contacting a sports university to see if they needed a Guinea pig. Although they are UK based, Loughborough University are an excellent institution and unlike US universities are not commercialised for a particulate big pharma or other enterprise.

Steve

Yes. I did contact one sports scientist because I thought they would be interested in the impact of someone doing such big distances but they weren’t.

As always a huge inspiration to me.

You are relentless in every way my friend!

How are you going to persuade Lis that you must do Round the world 😂

A huge ride to be proud of.

It’s mutual! I’d never consider an adventure race like you just did.

Lis has a message for you with regard to the round the world: “you are not being supportive of common sense”

Immensely proud of you, Chris! Fantastic achievement. Hope to see both of you in a few days’ time.

Fantastic write up cheers. I have really fancied riding coast to coast in Canada having done the TransAm race previously. Your comments about the bugs have confirmed my fears that this is not for me. What a great adventure.

I wouldn’t let that put you off! They are a small annoyance in the big picture of a great adventure. Just take mosquito spray and get a bug shirt.